Dr. Uta McKelvy, Extension Plant Pathologist, Montana State University

Dr. Audrey Kalil, Agronomist/Outreach Coordinator, Horizon Resources Cooperative

Dr. Mary Burrows, Associate Dean for Research and Graduate Studies, Virginia Agricultural Experiment Station

The North Central Integrated Pest Management (IPM) Center Pulse Crops Working Group and Montana State University Extension collaborated on a multi-year survey to determine grower practices and priorities related to pest management in pulse crops to better prioritize research and outreach material topics. This survey was designed by Jean Haley of Haley Consulting Services and delivered to growers, crop consultants, and Extension field faculty both digitally and in paper format at winter grower meetings in Montana, North Dakota, Idaho, and Washington in 2020 – 2024. Most of the survey respondents were from Montana. Questions would relate to pulse grower practices and experiences in the previous growing seasons, 2019 – 2023 respectively.

When respondents were asked what their greatest challenges were in pulse production, the top three answers were consistently weather, weed management and herbicide rotations, and disease management. From 2020 – 2022, some pulse production areas experienced significant drought, which exacerbated weed control issues and extended herbicide residual activity resulting in injury. On the other end of the spectrum, respondents also reported problems with too much rain leading to root rot and Ascochyta blight problems.

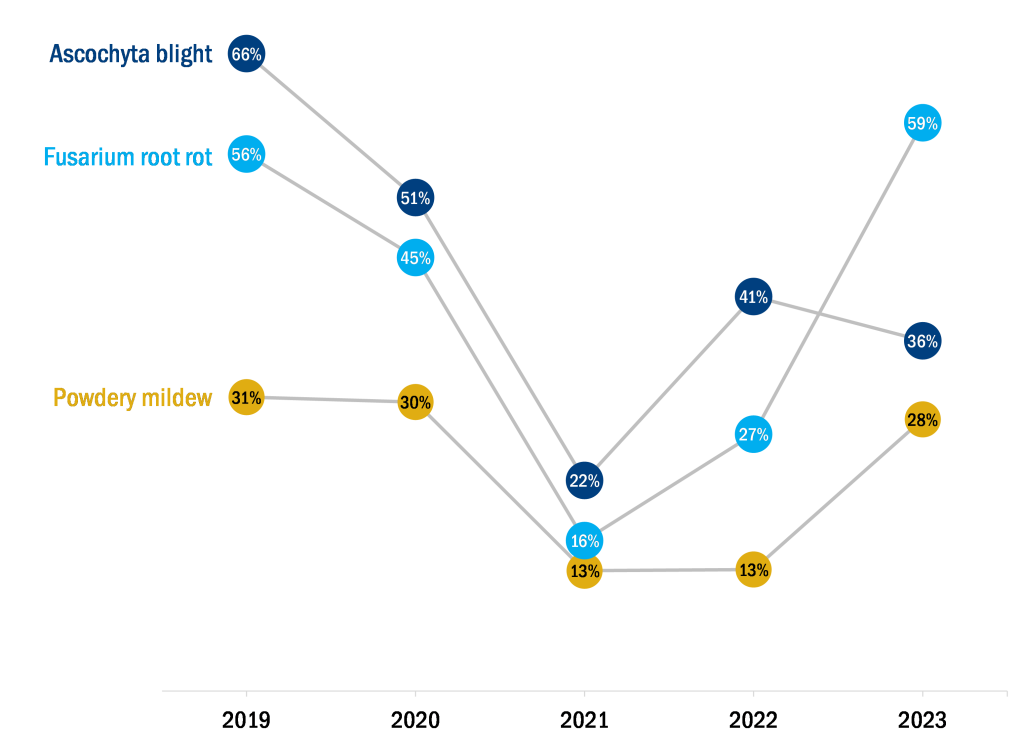

The top three diseases of concern across survey years were Ascochyta blight, Fusarium root rot and Powdery mildew (Figure 1). Ascochyta blight was consistently the number one disease of concern across years until the most recent survey year, 2023, when Fusarium root rot took the lead. Perceived disease pressure decreased for all three diseases from 2019 up until the 2022 growing season. This is likely associated with widespread drought conditions, especially during the 2021 growing season, that did not favor disease development. In 2023, perceived disease pressure for powdery mildew increased to similar levels as in the first survey year and we also observed a surge in perceived pressure from Fusarium root rot. Timely rains throughout the 2023 growing season likely promoted both diseases.

Figure 1. The top three diseases identified by respondents to the Pulse Crops IPM survey during each growing season, from 2019 to 2023. Surveys took place in the winter following each growing season.

Aphanomyces root rot pressure followed a similar pattern across years. At least some Aphanomyces pressure was reported by 30% of survey respondents for the 2019 and 2020 growing seasons. This decreased to 6% in 2021, and has increased since up to 36% in 2023 (Figure 2). The true disease pressure from Aphanomyces root rot may be higher than perceived because it is difficult to obtain a clear diagnosis in the field. Around 30% of respondents in 2024 reported not being sure if they are having problems with this disease on their farm. This number has been relatively consistent across survey years.

Figure 2. Percentage of survey respondents who perceived at least some pressure for Aphanomyces root rot in their fields from 2019 to 2023. Surveys took place in the winter following each growing season. Numbers in parentheses indicate number of survey respondents each year.

The primary means by which Aphanomyces root rot is controlled is through crop rotation. A minimum of five years between pea or lentil crops (six-year rotation) is recommended if Aphanomyces has been detected in a field. We asked the 2024 survey respondents about their crop rotation length between peas or lentils (Figure 3). The largest group of respondents, 45%, reported a three-year break (four-year rotation, e.g. pea – crop – crop – crop – lentil). A smaller group of respondents reported a one- (2%) and two-year (29%) break (two and three-year rotation). Even less reported the desired longer rotations with 19% and 5% of respondents reporting they leave four or five years between peas and lentils, respectively. Root rot management will improve as growers switch to longer rotations.

Figure 3. Reported pea/lentil rotation by 2024 survey respondents. Number of years is the length of time in between pea or lentil crops, e.g. pea – crop – crop – lentil represents a 2-year rotation. (n = 62 respondents).

We define Integrated Pest Management (IPM) as the use of multiple management tactics to keep crop losses to diseases and pests at economically sustainable levels. The goal is to improve pest management and increase yield while preserving our pest management tools (e.g. genetic resistance and pesticides). This approach is needed because very few tools exist for disease management in pulses and several pathogens causing important diseases (Ascochyta blight, Anthracnose, Pythium seed rot and seedling blight) have developed resistance to fungicides. In addition, important weeds including Kochia have developed resistance to multiple herbicides. The 2024 respondents prioritized crop rotation as an integrated disease management strategy, with 89% of growers saying they always use this IPM tactic in their pulse crops (Figure 4). Thus, shorter rotations reported in the survey may be on farms where root rot has not yet been an issue, or there is a lack of awareness around the rotation length needed to manage Aphanomyces root rot.

In 2024, 41% of respondents reported always using “identify the disease” as an IPM tactic, which represents a decrease of 22% compared to 2020 when 64% of respondents indicated always using this strategy (Figure 4). Moreover, 58% of respondents in 2024 only sometimes use “identify the disease ” as an IPM practice. This trend is concerning as identifying the cause of a problem is the first and most important step in developing an effective disease management program. Therefore, making diagnosis easier and more accessible could improve the management of root rot, as well as other pulse crop diseases. Other practices growers frequently use to manage diseases include crop rotation, scouting, seed treatments which help manage seed- and seedling diseases and support stand establishment, and agronomic practices which maximize crop health (Figure 4). Intercropping is a relatively new practice which growers are using to manage Ascochyta blight and root rot in peas, lentils, and chickpeas. The use of this practice has increased by 3% from 2021 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The frequency (always, sometimes, never) with which respondents have used these IPM strategies in their pulse crop fields within the last two years (data from the 2024 survey, n = 71 respondents).

When asked about their perception of IPM strategies over 90% of respondents in 2024 agreed that IPM is effective. This is, however, a decrease compared to the initial survey year where 97% of respondents agreed with that statement. This trend in the 2024 survey could be driven by an increase in root rot concerns among respondents (Figures 1 and 2), for which management strategies focus on prevention and avoidance but no options are available for in-season interventions. Respondents also agreed that IPM optimizes economic returns (93%) and minimizes environmental risks (94%), but there are still a portion of respondents that disagree that IPM optimizes chemical use (9%) and reduces health risks (14%). Pests and diseases can spread across operations, making it important that IPM is practiced across the pulse production community. Thus, it should be a priority to reduce barriers to IPM adoption.

There are many barriers that may prevent a grower from implementing IPM in their pulse crops. Overall, the percentage of respondents identifying major barriers to adopting IPM in their pulse crops has decreased for two-thirds of the barriers listed in Figure 5. “Lack of effective control” and “expense of IPM approach” have seen the greatest decrease as a major barrier compared to 2020, both by 12%. Researchers and Extension specialists have invested a lot of effort and resources into researching strategies for effective disease and pest management in pulse crops. Economic considerations including the cost of effective pesticides, cost of personnel, and risk of lower profits remain among the top barriers to adopting IPM practices since 2020 (Figure 5). Twenty-five percent of respondents report a shortage of trained scouts as another major barrier to IPM adoption, but this number has decreased by 4% since 2020.

Seventy-one percent of respondents in 2024 reported a lack of information about key pests as at least a minor barrier to adopting IPM practices (Figure 5), representing an increase by 13% compared to 2020. This emphasizes the need for the research and Extension community to continue to ensure information is available to growers and crop consultants so that they have the resources they need to properly diagnose disease and decide on appropriate and effective control tactics.

Figure 5. Barriers to IPM adoption reported by 2024 survey respondents (n = 60). Lack of information is highlighted in light blue as major barrier, because it has increased by 1% from 2020. The barriers highlighted in navy blue have decreased by 12% each in importance since 2020.

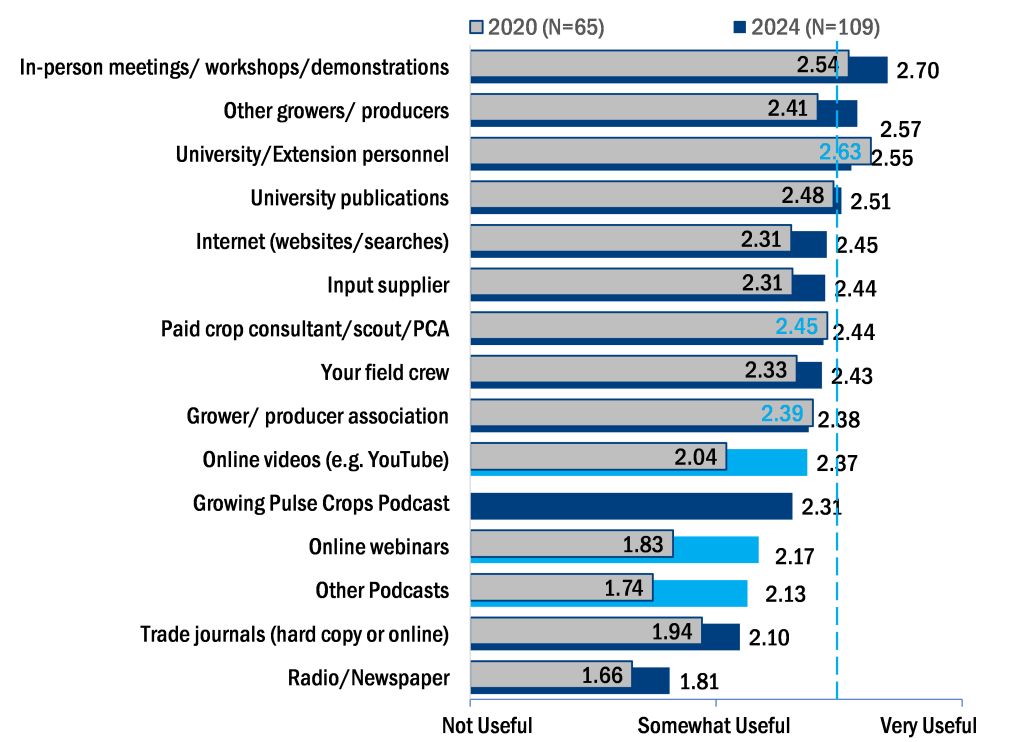

Figure 6. Respondents rated the usefulness of different sources of information for their farm operation. Light blue bars highlight sources that have increased substantially in 2024 compared to 2020. The Growing Pulse Crops podcast had not started when the 2020 survey was administered.

Extension educators and researchers have employed a variety of approaches to share management tactics and research findings with growers and consultants. Online resources (webinars, YouTube videos, podcasts) are used by survey respondents increasingly as these are typically low-cost and convenient (Figure 6). However, in-person meetings were preferred to online webinars, and growers may rely more on their peers than University personnel as a source of information (Figure 6). This reinforces our knowledge that trust is critical when it comes to making pest management decisions and while online/virtual resources are an important source of information, they cannot replace relationships that are formed through in-person interactions. In 2023, more respondents are using all the information sources we listed in the survey, suggesting that a diversified outreach approach will maximize the number of producers reached (Figure 6).

We are continuing the Pulse Crops IPM grower survey this 2024/2025 winter and ask for your participation. Your responses help us identify research needs and resources needed to support economic and sustainable pulse crop production. Your participation in this survey is entirely voluntary and anonymous, but greatly appreciated! You can access the survey by scanning the QR code below or following this link: https://bit.ly/pulses2025

Acknowledgments: The Pulse Crops IPM Survey is funded by a Specialty Crop Research Initiative grant from the National Institute of Food and Agriculture: U.S. Department of Agriculture (Grant # 2018-51181-28366).

Author Bios:

Dr. Uta McKelvy is an Extension Plant Pathologist at Montana State University. She obtained a M.S. in Plant Physiology from Martin-Luther-Univeristy Halle-Wittenberg, Germany, and a PhD in Plant Pathology from Montana State University. In her current role at Montana State Univeristy, Dr. McKelvy directs the Schutter Plant Health Diagnostic Clinic. Her applied research and Extension program focuses on the identification and integrated management of diseases affecting economically important crops in Montana, including cereals and pulse crops.

Dr. Audrey Kalil is an Agronomist and Outreach Coordinator with Horizon Resources Cooperative. She obtained her B.S. in Biology from the University of Minnesota- Twin Cities and PhD in Plant Pathology from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Dr. Kalil served as Plant Pathologist at the North Dakota State University Williston Research Extension Center for eight years. In this role, she led an applied research program focused on disease management in durum wheat, pea, lentil, and chickpea, as well as nodulation and nitrogen fixation in pulse crops. In her current role, Dr. Kalil works directly with growers to improve crop health and conducts educational programming.

Dr. Mary Burrows is the Associate Dean of Research for the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Virginia Tech and the Director of the Virginia Agricultural Experiment Station. She obtained her PhD from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and conducted a postdoctoral appointment with the USDA-ARS at Cornell University. She served as an Extension Plant Pathologist with Montana State University for 17 years, with three of those years serving as the Associate Director of the Montana Agricultural Experiment Station. Her research and outreach in Montana focused on cereals and pulses with an emphasis on diagnostics and integrated pest management.